Book Review of X-RAY ARCHITECTURE by Beatriz Colomina

BOMB Magazine, Spring 2019 Issue

X-Ray Architecture

Beatriz Colomina

Lars Müller Publishers, Zürich, 2019

Reviewed by Ashley Simone

The story is contagious and the imaging tells it:

Susan Sontag smiles at her notes on Frau Kloterjahn, the tuberculosis patient in Thomas Mann’s Tristan, while skulls are cracked open in the Jardin des Plantes of Paris, and Le Corbusier, clad in a swimsuit and smoking a pipe, boxes with Pierre Jeanneret on the beach. Later on, after groups of ladies—some in high heels, some barefoot, some in nothing at all—dance; Adolf Loos arrives, fresh from the sanatorium, and just in time: Frederick Kiesler is distributing marijuana and Woody Allen has finally shown up with Neutra and the orgasm machine. Greg Lynn comes late. In the end, following a multitude of “Blurred Visions” induced by the likes of Philip Johnson and Mies (under the influence of SANAA!), some clarity is found. But, before all of this, R. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion car was driven into George Keck’s Crystal House and then the house slowly disappeared (or did it?).

The cover of Beatriz Colomina’s speculative and multivalent book X-Ray Architecture features an image of a soft-looking protuberant form—Fuller’s Dymaxion car—visible through the facade of Keck’s Crystal House and its more sharply rendered floor plates and structural frame. The architecture—its envelope and tectonic quality blurred—is fading away. Bucky’s car occupies the nebulous space between inside and outside. It’s this ephemeral materiality and the questions it raises about exposure and privacy that lead to a proposition: “X-ray architecture is an occupiable blur.”

In X-Ray Architecture, Beatriz Colomina revisits and further nuances the connection between disease and modern architecture, in what she calls—playing on Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s “extra-canonical”—an “intra-canonical” reading of the Modern period. “Concealed within the standard narratives about modern architecture are other stories that have been forgotten or repressed, stories that energized and rationalized the work of the avant-garde.” Among a generous collection of images is the April 10, 1882, front page of the Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift, announcing the discovery of tubercle bacillus. Pointing to dormant and virulent origins, Colomina argues that the disease and its associated diagnostic imaging tool, the X-ray, shaped modern architecture. Her reading of the Modern period looks inward to reveal built evidence of the influence of disease and X-ray imaging—sanatoriums, white walls, roof gardens, pilotis; glass envelopes that materially alter public/private and interior/exterior relationships—while her lucid method of storytelling is outward-looking, delivered through the vantages of biology, psychology, biography, sexuality, and technology. The plot develops episodically across centuries beginning with Vitruvius, pausing to share the Victorian-era poem Lines on an X-Ray Portrait of a Lady, and ultimately suggesting that X-ray architecture is still very much at play today. Colomina observes that from Mies to SANAA, architectural thresholds have become increasingly ephemeral and ambiguous and may, in the face of contemporary mediatic craze, disappear altogether into a mushroom cloud of data. Finally, Colomina concludes by expanding the field. The “intra-canonical” examination, which reveals a “parallel” development (it may actually be ever-so-slightly oblique) between X-ray technology and modern architecture, implies a broader and forward-thinking set of questions that include: How does architecture absorb transformations of public and private and reflect on those transformations? Should we be designing new architecture or new bodies?

Whatever the case, a new theory of architecture is on the horizon. That is if architecture, under siege by some other contagion, doesn’t disappear first.

Susan Sontag

Lessons of anatomy of the baron Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), in the Jardin des Plates of Paris, circa 1800

Adolf Loos after a stomach operation, Sanatorium der Kaufmannschaft, 1918

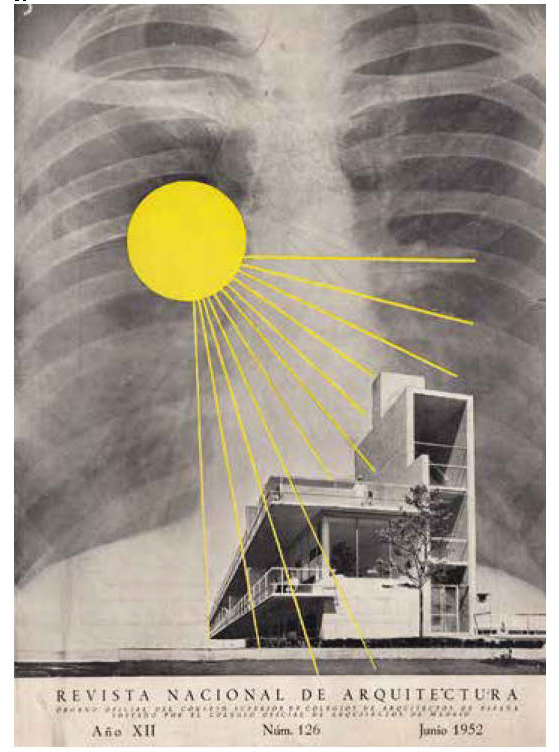

Cover of Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 126, June 1952

SANAA’s installation in the Mies van der Rohe Pavilion, Barcelona, 2008